How can we cultivate energy and harmony in late life? What does it mean to flourish? Now I am in my early 50s, wondering what I still need to learn.

I will start by summarizing and integrating my reflections and revelations concerning the creative life of my grandfather, Konosuke Masuda (1916–2000), to find — and share — inspiration. Curious about Masuda’s construction of a beautiful, involved, and extensive worldview, I discovered certain sustained practices of his that act as missing pieces of my puzzle. These involve the development of creativity in late life by applying a core assumption of embodied theories of mind: the dynamics of our bodies affect cognition. It seemed at first like a puzzle only inside my head, but it turned out to be a puzzle that requires me to use my body to solve.

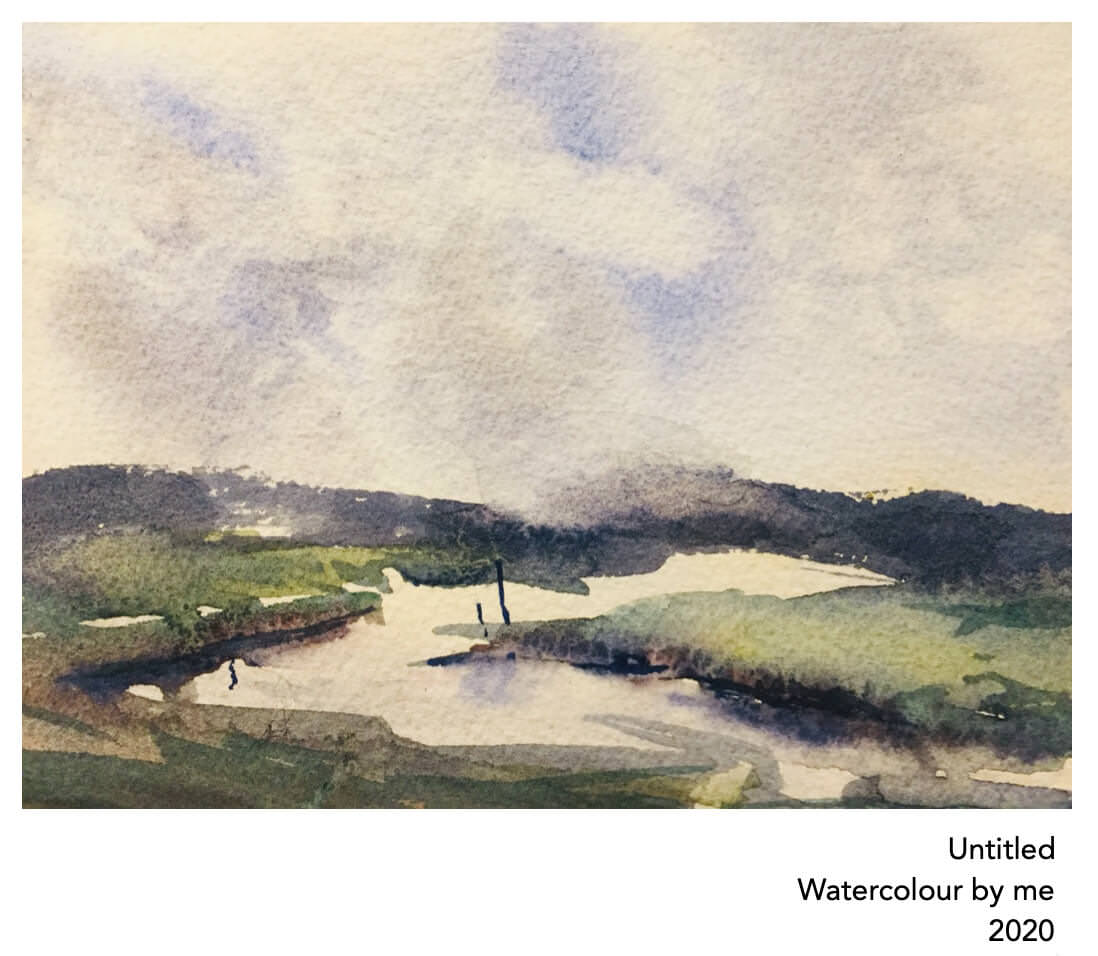

This is reflected in my own life experience. I was a scientist, suddenly paralyzed at the age of 40, at the height of my career, which was unusual and tragic. Then, confined in my wheelchair, I made a 180 degree turn to explore the arts and proceeded to build an art-based community to bridge and nurture both logic and emotion. I continue to expand and refine this community. But lately, I have become interested in how artistic acts, such as making figurative renderings of nature, can be as a means of developing new insights, consciousness, and empathy. My sudden fondness for representational art in my 50s is very perplexing and existential. I am considering several possible explanations for my change of heart.

Tracing in brief the lineage of the theory that cognition is embodied, which has only been studied empirically in the last few decades, there is no shortage of guides. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), one of the greatest writers of his time, is lesser known as a painter. He exhibited a largess of embodied knowledge over the course of his life. And he painted things, especially landscapes, that he consciously observed in the sensory realm as both a manifestation and a means of cultivation of his artistic vision. He was well aware that his practice of pictorial art, coupled with observation of the dynamic processes found in nature, played a significant role in his understanding of science and the development of his artistic vision. Interestingly, Goethe mentioned in his autobiography that his childhood environment was partly responsible for his lifelong passion for art. In the midst of the Seven Years’ War, the ten-year old Goethe’s bedroom was converted into a studio for the Frankfurt Painters, which gave him the rare opportunity to closely observe painters at work over a period of two years. He wrote:

“The eye was, above all others, the organ with which I seized the world. I had from childhood on lived among painters and had grown used to looking at objects as they did, in relationship to art.”

Echoing Goethe’s reflections, I cannot help but attribute a part of my enthusiasm for art to my own living arrangement, which felt deep, lasting, and significant. I was born and grew up in my grandparents’ house until I was 6 years old, when my parents built a new house a few blocks away from my first home. I was always around my grandfather, whether he was doing his plein air painting or sitting in his quiet study filled with oil paint fumes. However, as a child or young adult, I never really understood the world he created until, most recently, I began to learn how to paint.

Now, it is so thrilling to realize that the world he saw and understood is in those paintings, and in the poetry he produced. Moreover, through my act of painting, I am beginning to share a similar sort of interest, care, awe, energy, humility, gentleness, and some of the discoveries that shaped my grandfather’s late life learning. That is the magic of the art.

Since I started watercolour painting, I’ve discovered that the act of painting changed the way the world looked to me and vice versa. Quite literally, the act of painting can change the colour of the light I see, the space I see, and the nuanced things I notice. Like most people, I used to be happy with the idea that art belongs to masterful artists and critics who have levels of understanding and expertise that are beyond the lay public. In a slightly different way I was also completely happy with the way I was appreciating art rather distantly, as a spectator, and had neither a personal connection nor any curiosity about how I could learn artistic skills from them. I was like someone who loves to eat at 5-star restaurants but has never wanted to cook. I now have a different relationship with the things I observe; the sky is rarely pure blue or the clouds pure white.

“ …the act of painting can change the colour of the light I see, the space I see, and the nuanced things I notice.

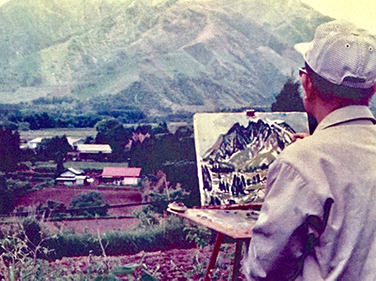

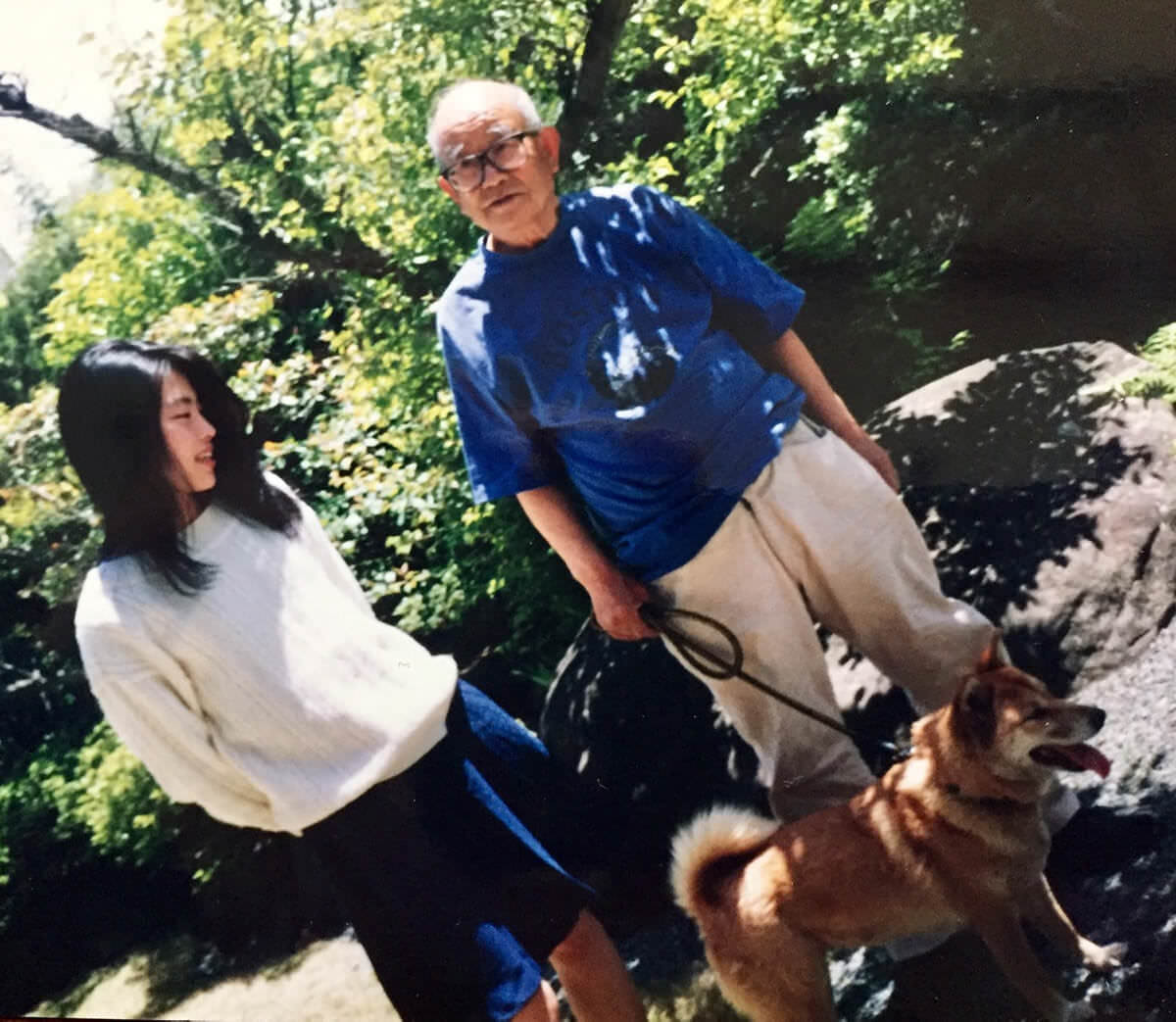

Back to my curiosity about my grandfather: He was a banker by trade, a “lone-wolf” when he was young, and a bookworm throughout his life. He was also a meticulous note taker and always kept a pen and a small sketchbook in a chest pocket. After his retirement from the bank at the age of 53, almost my current age, he worked as a corporate executive in a chemical company for another 17 years. Since his early 50s, he became increasingly more passionate about his hobbies, such as plein air painting, reading, writing, Bonsai, photography, fishing, Go (the Japanese board game), and travelling. He always painted the places, objects, and people where exactly he found them. I vividly remember his wooden, leather handled oil painting briefcase, which travelled with him everywhere. He left over 1,000 oil and watercolour paintings, countless poems and sketches, and also a self-published memoir that documents his detailed experiences of WWII as a private, and how strongly he condemned that unjustifiable war.

One of the things I realized most vividly while recounting memories of my grandfather and going through his paintings and poetry about nature, was his way of observing the world with inner contentment. At every moment, he is observing the changing landscapes not only as an artist, but also as a naturalist. It is not an exaggeration that he spent most of his free time in nature, especially in his splendid garden that attracted birds and dragonflies. He wrote a poem at age77:

欲もかれ(枯) 自然や花に 喜びを

絵筆とるとき 新たな命 (平成5年2月)

(My translation):

Even though I have lost my desires, I still find joy in nature and flowers

When I hold my paint brush, I renew my excitement in life. (February 1993)

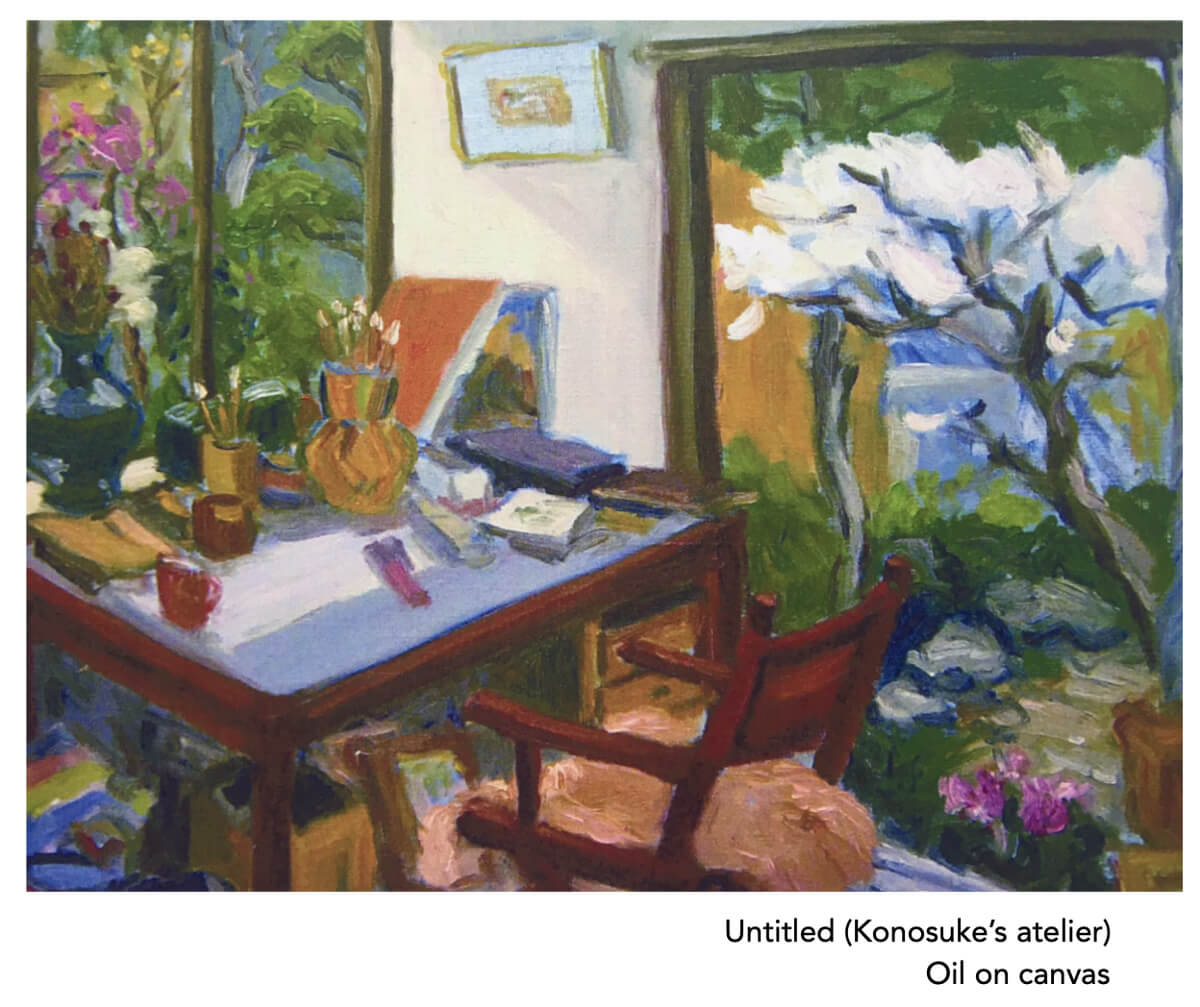

The oil painting depicts his sun-filled atelier adjacent to his garden he designed and maintained with constant care on his hands and knees. This painting, in early Spring, (perhaps February) shows the big old plum tree with white plum blossoms about which he often wrote poems. That tree produced many plums year after year, which my grandmother made into Japanese salted plum, my favorite food (just thinking about it makes me salivate!). The yellow-flowered tree in the distance emits intense fragrance, I so fondly remember. Although he was an amatuer painter, he skillfully conveyed his presence and feeling.

I feel his corporeal presence in a wooden armchair with fluffy upholstery as if it represented his warm and humble character. The positioning of the chair, slightly removed from and perpendicular to the desk, surrounded by a garden through the large widows, conveys his sense of readiness, his studious nature, and his fervent love of the natural worlds. On the desk, I see the simplest, most ordinary objects around him, which now unleash my memories — pens, paint brushes, notebooks, books, verses, flowers, radio, tea cup, and a work-in-progress canvas revealing a partial image of Mt. Aso, the subject he painted the most. All of these represent his state of mind. I really like how he used the weight of whiteness to render the morning sunlight hitting half of the desk surface, echoing the intense colour of robust plum blossoms. That gives the painting not only visual balance but also a certain meaning — a feeling of having arrived at a place of freedom, awe, and regenerative energy, like the Spring season.

The painting of his garden depicts the arrival of autumn with some bright-color foliage. This garden was my childhood playground. I used to sit at the edge of the pond for hours, enjoying colourful Koi. Every summer, we used to clean the pond, which was a whole-day family event involving emptying the water and scrubbing and removing the accumulated moss at the bottom and sides of the pond. As a child, the highlight of cleaning the pond was catching those large Koi, about 5~6 of them at least, with a landing net in order to keep them in a large bucket while clearing. Oh, that was a big deal. I still feel the sensation of the agile, slippery Koi moving in my hands.

The painting makes me nostalgic about those days and the place, and Koi which illuminate vivid, precious childhood memories. Is it only in my imagination that the saturated golden, scarlet, and brown foliage repeats the colours of Koi I used to play with? Did Konosuke subconsciously paint the autumn garden in the colours of the Koi he treasured? The pond looks mysterious; there is no reflection of the foliage — no shadow of Koi under the deep blue water and large rocks. Did he forget to paint them? I am convinced that his emotional connection to the Koi and trees and birds never left him, even after the Koi disappeared.

To what extent did Konosuke’s sustained artistic practices endow him with the strength to overcome his natural fragility, up to the moment of his death? This question haunts me now. He died of gastric cancer when he was 84, five year after his gastrectomy at age 79. In hospital, he continued to paint, write poetry, and take notes. On the morning of his surgery he wrote:

手術を前に 年令(よわい)八十 いろいろあるが

生きざまん 己を通して 我れ悔いなし (平成七年6月5日)

Right before my surgery, nearly there, my 80-years-old mark. Even though I am battling illness and the spread of death before me, I am truly living my life through all my senses. I have no regrets. (June 5th, 1995)

His physical health started to slowly decline after his cancer diagnosis. I started feeling guilty about my grandparents, whom I loved most in the world yet left behind when I moved to New York City in 1994, when he was facing his health ordeal. I was afraid to admit to myself that I should not have been so self-absorbed in my life and “abandoned” those close relationships. When I found this poem, which captures his moment of frailty, I felt consoled. Truth can free us. I found the delicacy of this poem tricky to translate into English. Perhaps some of its deeper meaning escapes translation. I had an extensive discussion about its meaning with my uncle (one of Konosuke’s sons) who is just a phone call away.

老いぬれば 心乱れて みぐるしく

やがて我もと 思えばかなし (平成八年2月)

I am anxious about losing control and freedom (to create) as I am growing frail. One day I, too, might lose human dignity, and I feel so sad when I think about it. (February, 1996)

Konosuke was getting old but did not stop what he loved to do — plein air painting. Nature seemed to have a positive effect on his emotional state, stimulating cognitive activity. The following year, he wrote:

水ぬるみ 菜の花も咲く 江津湖にて

スケッチなどして 今年も遊ぶ (平成八年3月30日)

Water has been lukewarm and the Canola plant is flowering

I am sketching at Ezuko Lake. Let’s play this year, as well. (March 30, 1996)

石佛は やさしくおわす 吾が命

あと幾日や 絵がく生きがい (平成八年9月19日)

The sculpted stone Buddha (in a garden) is looking at me kindly, compassionately. How many more days will I live? Being able to paint feeds my spirit to live. (September 19, 1996)

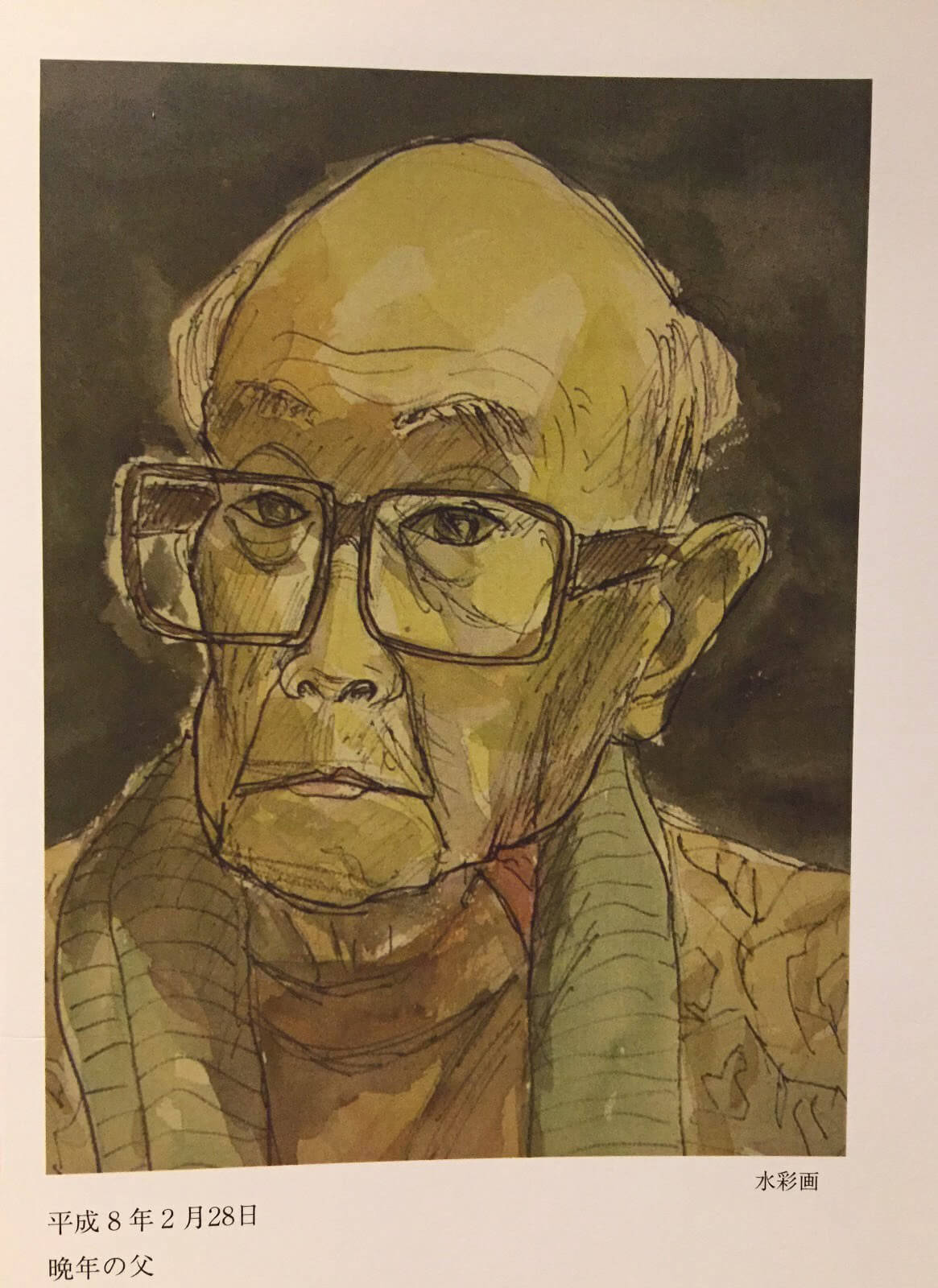

As I revisit his work, I continue to be astonished — not only by his forbearance and determination to create, leaving no room for despair, but also by his unfailing sense of awe and wonder, even when he was struggling with cancer complications. It is safe to say that his sustained artistic practice trained his mind and body to respond with awe and wonder to the world around him. His poignant self-portrait that year touches me deeply.

“In order to understand what is going on in the world, you use not only your sensory information, but also your motor experiences. You need a body in order to acquire the motor experiences that you can then use to interpret actions performed by others,” explains Giulio Sandini, Director of Research at the Italian Institute of Technology and Professor of Bioengineering at the University of Genoa, Italy.

Ultimately, though it may seem a cliché, we bear witness to Konosuke’s inner transformation through his painting and poetry and affirm that our cognition isn’t confined to the cortex but is determined by our direct bodily experiences in the physical world.

Konosuke was gentle, kind, and patient, and most of all, a diligent student of spiritual pursuit. In late life, he often recited the word, ‘Mu-shin (無心)’ — a state of mind free from delusion. He did not bother anyone about the details of his sufferings; instead, he consciously sought to experience a sense of enormous emptiness by exposing himself to nature and all living things.

“ …he consciously sought to experience a sense of enormous emptiness by exposing himself to nature and all living things.

When he was 81, battling advanced cancer, he painted this almost abstract, figurative interpretation of the very active Nakadake Crater in Mt. Aso which he loved to paint the most. His medium shifted more from oil to watercolour toward the end of his life, as oil painting takes more time to complete. Also, his compositions and motifs in his last few years were becoming more abstract and simplified. His life-long plein-air practice helped him develop an enhanced visual memory and quick sketching skills, because environmental conditions are unstable. I wonder if plein-air also prepared him internally to embrace the change that included his imminent death. In this painting, Konosuke takes us inside himself, as he, in turn, is inside chaotic nature. Vast space and dynamic movement of the crater smoke remind us of constantly changing, diverse, complex reality and our own impermanence. I imagine his artwork and thinking evolved together, leading him to peaceful, noble self-transcendence.