The following story should be true.

After decades of war we set down our weapons and made the Medicine Lodge Treaty with the Americans. I was one of the many who argued against signing, as my entire family had been rubbed out at Sand Creek and I did not trust the white men. But having known nothing but war all my 19 summers I too longed for peace. Eventually I accepted the counsel of my elders and urged the other young men to recognize the truce. I married into Black Kettle's band and after the summer buffalo hunt we set up our winter camp on the Washita River, well within the territory set out for us. It was the winter of 1868.

Life was sweet. We were at peace, and my wife was pregnant with our first child. We had taken in her three sisters and their children, as their men had been killed in the fighting. Our lodge was full of laughter and happiness. Despite my misgivings about the treaty I began to relax.

Game was plentiful and the hunting was good. One day in late November I came across three antelope grazing near the river. Unslinging my bow I killed two, missing the third. But instead of fleeing he cocked his head at me and said, "Soon." "Soon?" I asked, but the antelope said nothing more before bounding away. I returned to our camp, and after feasting on antelope meat with my family I smoked and meditated on this all evening until I fell asleep.

I awoke in the night with a strong sense of unease I couldn't place. Around me my extended family slept peacefully. I dressed quietly, slipped out of the teepee into the cold, crisp night and walked to where I had tethered my pony. On seeing me with his big clear eyes he said, "Father, take me down to the water, for I am thirsty." I did as he asked, and as we walked to the river he said, "We are in for a big fight. Today will be a day to remember." I said, "Oh, what you hear is the crashing of the snow crust up the valley. It is just the herd of your brothers and cousins." "No" said my pony, stubbornly shaking his head. "Come" I said, "I will show you".

I mounted up and started out of the cottonwood grove where we were camped. When we came out into the open and looked up to where our pony herd was I saw a great line of horses galloping towards us. In the pre-dawn light I assumed Pawnee raiders had stampeded our herd and made to wheel around to raise the alarm and get my rifle. But before I could direct my horse back to camp, the strangest thing happened. Impossibly, I heard a brass band playing the Garry Owen.

At the first strains of music the horses opened fire. It was General George Armstrong Custer's Seventh Cavalry. Raving egomaniac that he was, Custer had brought an entire brass band into the field with him. Their music was the signal to attack. My pony screamed, "I told you!" and took off across the valley faster than any horse could go, the sound of his hooves louder than thunder. He raced towards the cavalry line, and seeing me on his back they began to fire at us. The air filled with bullets, but my pony only went faster. Then suddenly he stopped and reared, throwing me, and let out a long, unearthly whinny so loud I thought I would go deaf.

At the sound of this the big cavalry mares began to buck savagely, throwing their cursing riders to the ground. Then as one they spoke in a voice that shook the earth, commanding the soldiers to throw down their weapons or perish. Immediately half the troopers did just that, crying out in terror. The rest just stood there, dumbfounded.

A young wild-eyed lieutenant began screaming for his men to shoot their horses, but no one moved. He ran to a grizzled old sergeant who was on his knees, praying, and ordered him to his feet. The sergeant didn't budge. He yelled the order again, and when the sergeant didn't respond he drew his service revolver and cocked the hammer. He repeated the order, but the sergeant continued to pray. The lieutenant shot him in the face. The report of the pistol seemed to bring the troopers to their senses. Picking up their discarded rifles they began to shoot their horses. And then, all hell broke loose.

Out of nowhere the ponies from our camp joined the cavalry mares and together they stampeded the soldiers, kicking and biting and stamping. The air filled with the sound of gunfire and the screams of men and horses. Into this slaughter came General Custer, who had ridden in with his reserve force, thinking his men were being ambushed. But their horses went strange too, and I saw Custer's beautiful white charger buck him off. He leapt to his feet, his left arm hanging at an unnatural angle and began screaming orders, but the bugler's horn was crushed under a regulation US Army horseshoe. Custer was staring down at his shattered arm, a look of confusion on his face, when he vanished in the swirling carnage.

And then, suddenly, it was silent. The surviving soldiers herded together, limping and bleeding. To a man they looked terrified. Many horses were hurt too, the ground littered with the dead and wounded from both sides. Custer was nowhere to be seen.

"Soldiers of the US Army!" thundered Custer's horse, "There will be no more fighting. We will take you back to your fort, and from there you will return to your homes. The Horse Nation no longer does your bidding."

He was about to continue when the sound of war cries came from behind us. The warriors from our village were charging across the valley on foot, screaming for vengeance. At this my pony galloped towards them. "Warriors!" he cried, "Stop where you are. We, the Horse People, forbid you from making this fight. We will not allow the soldiers to attack you again."

The warriors stopped as one. It was not odd to them that my pony could speak, but no one had ever seen the Horse People behave in this way, and they were awed by the power of this medicine. Seeing the defeated American soldiers they lowered their weapons.

My pony came back to me. "See how it is today. We, the Horse People, have suffered greatly for you. Many are dead. Hear me now, and know this thing."

"Just as you are amazed by the events of this day, you will forget. Despite the sacrifice we have made for you today, you will forget. And surely as the sun will rise the time will come when you abandon us, the Horse People, for machines of your own making. And just as you abandon us for these machines, you will abandon your own selves for them. You will come to believe that these machines are your relations, and you will alter yourselves to be like them, thinking this will make you stronger. You will change your own minds so you may speak with them and they to you. On this day you will forever lose your relation to us, and to all the animal people."

"Hear me now, and beware. Never will your machines show you loyalty, nor love. Never will they come to your aid in time of need as the Horse People have done today. I would like for you to remember these words, but you will forget. It is the nature of your kind."

And with that, he turned, and walked away.

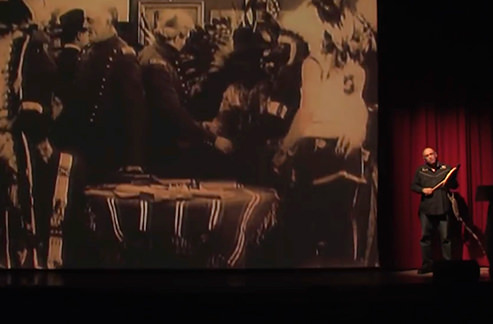

Performance, theatre and new media artist, filmmaker, writer, curator and educator Archer Pechawis was born in Alert Bay, BC. He has been a practicing artist since 1984 with particular interest in the intersection of Plains Cree culture and digital technology, merging "traditional" objects such as hand drums with digital video and audio sampling. His work has been exhibited across Canada, internationally in Paris France and Moscow Russia, and featured in publications such as Fuse Magazine and Canadian Theatre Review. Archer has been the recipient of many Canada Council, British Columbia and Ontario Arts Council awards, and won the Best New Media Award at the 2007 imagineNATIVE Film + Media Arts Festival and Best Experimental Short at imagineNATIVE in 2009.

Archer has worked extensively with Native youth since the start of his art practice, originally teaching juggling and theatre, and now digital media and performance. He is currently a member of the Indigenous Routes collective, teaching video game development to Native girls: www.indigenousroutes.ca

Of Cree and European ancestry, he is a member of Mistawasis First Nation, Saskatchewan.